A full carton of eggs sits alongside the stove.

Every Sunday my mother passes them around, one egg for each child, one for her and two for my father.

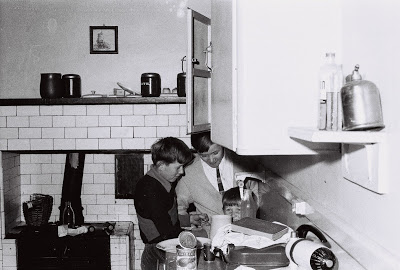

She cooks his first in the fry pan alongside a butter soaked slice of bread. Then the brothers each take it in turn to cook theirs. My older sister prefers to boil her egg, hard boiled, the egg yolk as yellow as the sun.

My mother scrambles the little ones’ eggs into a buttery spread at the bottom of a sauce pan.

I take my egg to the corner of the kitchen away from the others and crack it gently on the side of a tea cup. My older sister has taught me how to ease apart the shell with my thumb and finger, so that the inner skin holds like a hinge when I pull the shell back. I can then tip the yolk from one half of the egg shell to the other, letting the white slide into my tea cup.

All the while I keep a close eye on the yolk, not only for blemishes, those red blood blisters that might signify a fertilized egg gone wrong – one I will not eat – but also for ruptures. I must preserve the skin to keep the yolk and white from mixing. The yolk glistens and slips from one side of the shell to the other.

When all the white has slid away into the cup, I offer the yolk to one of my brothers to cook alongside his own. Sometimes the brothers fight over it.

Then I take a fork and a spoonful of sugar – two spoons depending on the size of the egg and amount of white I have collected – and begin to whisk.

It is a tricky business. I must tilt the cup to one side to get maximum egg white under the whisk without spilling any.

I do this for an hour or two. I do this till the kitchen is empty of breakfast eaters. I do this till well past the time when the eight o’clock, the nine o’clock, the ten o’clock Mass are over, by which time it is too late to eat.

I must fast for three hours before Mass and communion, otherwise I will be in sin.

Today, my youngest daughter tells me she is in trouble because of my eggs.

‘It’s your old eggs,’ she says. They’ve caused my allergies. Your old eggs make me the sickly one in the family.’

It is a joke perhaps, but if I am to take it seriously what is she saying? That I should have conceived her earlier, just as I should have begun to whisk my Sunday morning egg at six o’clock in the morning in order to eat it in time for the last Mass at eleven.

I did not plan to have this daughter so late in my life. At the time I called her an afterthought, almost by way of apology, but the Sunday egg became a tradition for me, however late I came to eat it.

Put off the best till last, my mother said. Always save the good stuff. Do all the hard and horrible jobs first and then you will have the greater pleasure of anticipation.

All those years ago when I came home hungry from Mass and went to collect my egg white from the fridge, it still sat in its cup like a fluffy white cloud, but the cloud no longer stuck to the sides. The cloud had come away and slid around the inside of the cup afloat on a trickle of liquid that had leaked its way out, like a rain puddle.

I think my mother is wrong. I think my daughter may be right. There is a point in taking in the best things first. If you wait too long they might spoil.

When I think of the warmth of a freshly laid egg in the cradle of my hand, the warmth of the egg that has just slipped out from its hen mother’s body onto the straw of the hen house, only to land in the cold outside air, I remember my daughter’s birth.

How she hung there upside down in the doctor’s hands, after a quick labour that had surprised us all. Her body slimy and purplish blue. In those first few moments, her first in the world, I wondered through the fog and haze of a painful labour, will she ever breathe?

And then came the cry, the loud scratching sound that is a newborn’s cry, and I could let myself think the unthinkable.

If she had left the best till last, if she had held off that first breath, then she would not be here today to complain about her mother’s old eggs.